Here is a lovely English jig, “The Scotch Cap,” which was originally published in the “English Dancing-Master” by John Playford in 1651. It is a great tune to play on the dulcimer. I uncovered dulcimer tablature for this tune while sorting through an stack of music which I’d set aside to “learn sometime.” The tab is from Mike Casey’s workshop at one of the Appalachian State Dulcimer Workshops which I attended years ago. The jig is mesmerizing, haunting and very addictive. However, the melody doesn’t quite sound like it is written in either a major or minor scale. So, I wrote down all the notes and did a “Google” search. I found that the tune is written in the Dorian mode. That led me into a “deep dive” to learn about the Dorian mode. I wrote out my own dulcimer tablature for “The Scotch Cap” using the 1-1/2 fret (I’m cheating here) and find that the song very easy to play on the dulcimer. That’s good, as jigs are often played at a spritely tempo. I also give an explanation of the basis for a “mode” and our mountain dulcimer “diatonic” scale. However, if you are not interested in music theory, just skip to the song at the end of the post!

About “The Scotch Cap”

The “cap” in the title of this song could refer to a traditional Scottish cap, or perhaps the crowning of Charles I in Edinburgh. In old Scotland, it also refers to a type of cap worn by prisoners which covered their face so they couldn’t communicate with the other prisoners. In any event, I did not find lyrics for this tune; it is strictly a dance tune. The “caller” would presumably be shouting dance steps to the dancers.

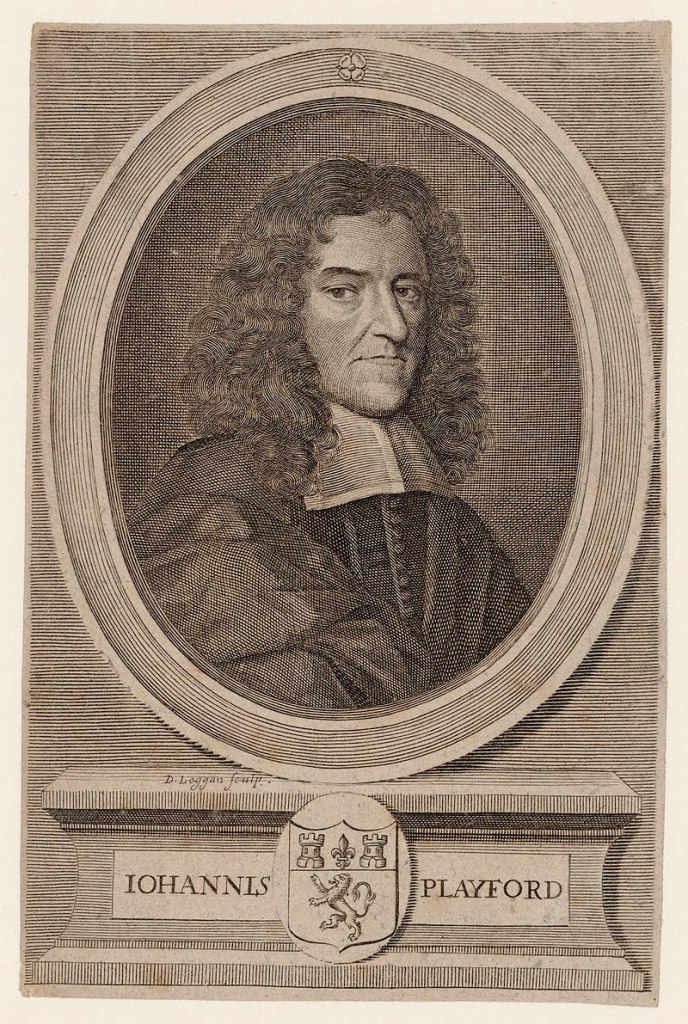

“The Scotch Cap” is a traditional English country dance. It dates back to the time when these jigs and country dances were popular. It was published in, “The English Dancing-Master,” by John Playford, an English publisher, in 1651.

John Playford (1623 – 1686) was the most important and influencial music publisher of his time. He was a bookseller, minor composer and important publisher, whose book publications ranged from music theory, instructional books for several instruments. He was friends of most of the best known English composers of this period.

The “English Dancing-Master” published in 1651 was his best known publication. It was widely used by the public and was the principal source of knowledge of English dance steps. The book included the melodies and dance steps for 104 tunes set to the fiddle. It was so popular that it went through 18 editions. The last edition, published in 1728 by John Young, held about 700 tunes.

Here is the original song in the “English Dancing-Master” with the dance steps. The title is listed as either “Scotch Cap” or “Edinburgh Castle.”

What is an English Country Dance?

This excerpt from the “The Folk Dance Federation of California” gives a good description of English country dances: “Country dances are a type of dance that were danced both by country folk and in courts beginning in the late Renaissance and continuing into the 18th century. They have a number of steps in common, but each dance quite often has steps unique to that dance. Country dances in general are an evolution of the bransles, and have some steps in common with these dances. Country dances originated in England, and later spread to Germany and France.” (Source: https://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/del/sections/english_country_dance.html )

Music Theory? Yikes! Get more help!

Musical theory and terminology can be quite daunting to a person who is just learning to play the dulcimer. Without a musical background, it is basically like learning a new language — or at least new terminology. However, acquiring some understanding of the dulcimer’s fretboard arrangement, scales and modes can help make sense of playing music. I encourage anyone who likes to know the “why’s and how’s” of it all to take a deep dive into modes and scales.

Along my dulcimer journey, I am self-taught. A number of mountain dulcimer books containing explanations of the modes and scales served as my “teachers.” I enjoyed the tune examples given in the books to demonstrate each of the modes. These books are still relevant and make good references for learning about modes:

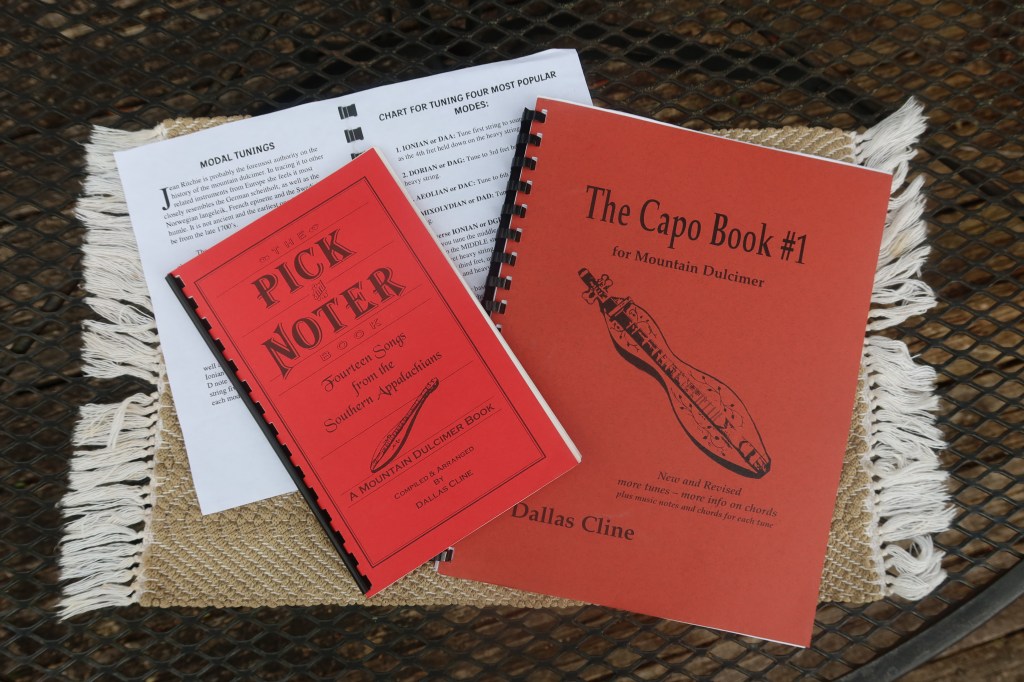

- Dallas Cline’s book — Although called “The Capo Book #1,” it gives a great explanation of the seven modes and includes lots of song examples.

- Dallas Cline — “The Pick and Noter Book” — 14 tunes from the Southern Appalachians in different modes and dulcimer tunings.

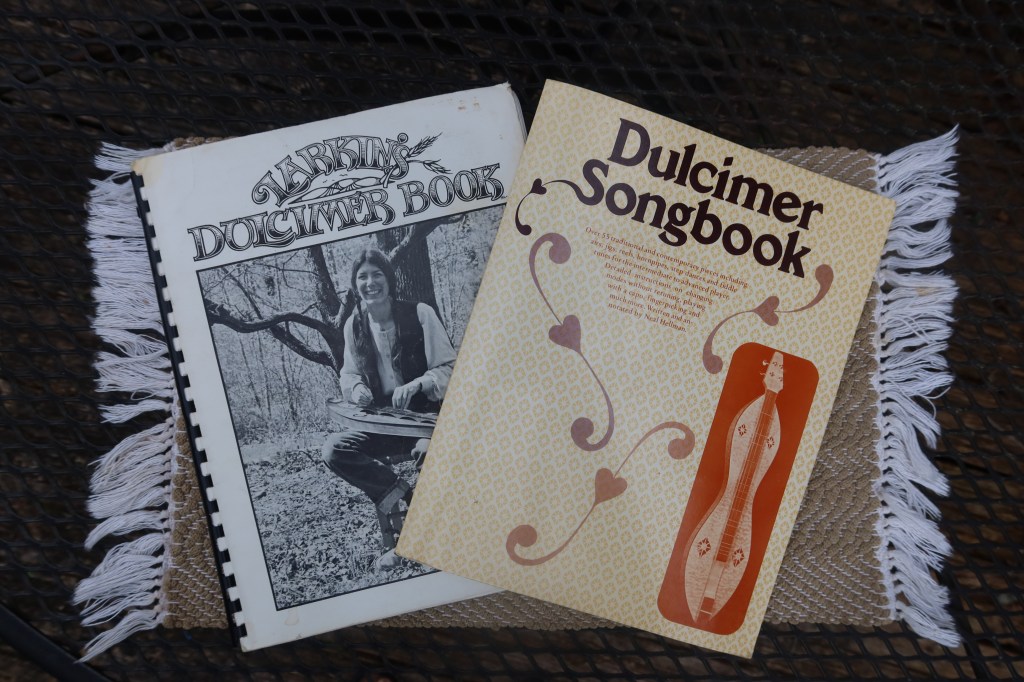

- Neal Hellman — “Dulcimer Songbook” includes songs in different dulcimer tunings and modes with some explanation of modes.

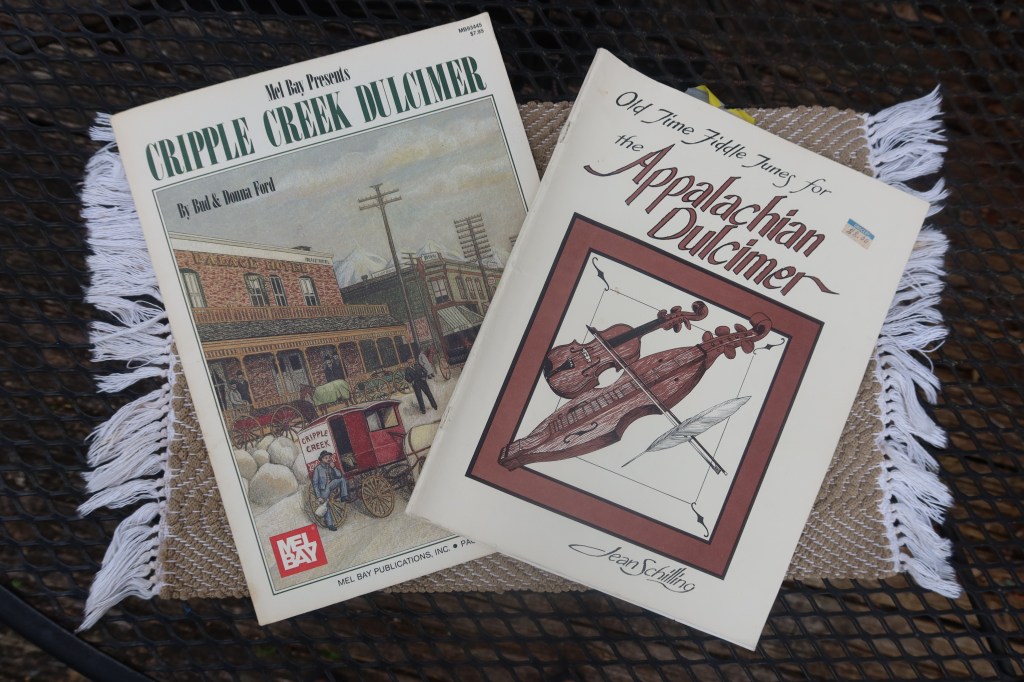

- Jean Schilling — “Old Time Fiddle Tunes for the Appalachian Dulcimer” is a great reference of Appalachian mountian dulcimer tunes and as well as lots of interesting stories with tunes listed by their modes in various dulcimer tunings.

- Jean Ritchie — “The Dulcimer Book” lists songs by their “modes” and includes explanations of modes and her tunings in the book.

- Jean Ritchie — “Dulcimer People” gives interesting stories in people associated with Applachian music, the history of the dulcimer, a brief explanation of dulcimer tunings/modes and many tunes (but not all with dulcimer tablature).

- Larkin Bryant — “Larkin’s Dulcimer Book” is a dulcimer “standard.” I still refer to the chord charts in the back of the book. The book gives a short but easy to understand explanation of modes. Lots of songs in DAA and some in DAG (D Dorian) as well as other tunings.

- Bud and Donna Ford — “Cripple Creek Dulcimer” tunes their dulcimers to GDD (Ionian Mode) and gives examples of a number of songs in this tuning. Then the Ford’s go on to give explanations of tunings for all the other modes with examples of songs in each mode (Ionian to Locrian). Chord charts are given for these modes — just extrapolate to get to other string pitches. Good luck!

Notice that all these books were published years ago; most are probably still available in certain dulcimer shops, publishers, on-line. etc. With increased interest in use of the DAD tuning and capos, I find that current tablature books don’t often explain the different modes or list songs according to their playing mode. But, modes are still relevant today. Plus, the modes help to explain the dulcimer fretboard. If you have one of these books, it is worth exploring the information in the books.

About Mike Casey

Mike Casey, who hails from North Carolina, is someone whom I briefly encountered in my days of attending the “Appalachian State Dulcimer Workshops” years ago in Boone, North Carolina. I took several of Mike’s workshops during the weeklong dulcimer events. As I recall, Mike Casey was one of the more accomplished dulcimer instructors teaching at the conference, and was an especially skilled fingerpicker. It is my understanding that, over the years, Mike developed quite an expertise regarding Irish music including playing the whistle and flute. He also authored a book, published by Mel Bay, which contains a series of exercises for developing skills in fingerpicking and flatpicking on the mountain dulcimer. At the end of the book, he includes 13 tunes for practicing these skills. “A Scotch Cap” is included in A Dorian/Aeolian. The book contains a great set of tunes; I wish that he had published more tunes and that I could have gotten to known him better at festivals around the country.

Back to the Dorian Mode

Back to the “Dorian” Mode. As we see from “The Scotch Gap” which was published in 1651; the Dorian mode is an old musical scale. The Dorian Mode has been used in music for centuries particularly from the Medieval period through Renaissance times and including the comtemporary genres of folk, jazz, and rock music. Music played in the Dorian mode has a melancholy, mournful tone, yet somehow a “happy” aspect to some of the notes. It is perfect for those haunting Appalachian songs.

There are seven of these “modes” or musical scales which date back to ancient Greek times. The Greeks entitled the modes as: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian. Each one of these modes starts on a different note of the musical scale and has a different and unique pattern of notes. On the dulcimer, we use several of the musical scales more often than others.

Here’s my best attempt to explain the Dorian Mode and Music Scales:

“Music to our ears” really means “music to our western trained ears.” Since we were born, our ears have become used to hearing western music and certain tones and sequences of tones. Contemporary music is formed around a “major scale”, or sequence or pattern of music notes, and a “minor scale” or a similar sequence of notes.

However, through the ages, these are not be the only scales which musicians used. Some earlier scale patterns date back to ancient Greek music theory. These are termed “modes.”

To understand the differences — and where the mountain dulcimer fits in — I like to use the analogy of a contemporary keyboard and piano.

What is a Western scale?

A scale is a series of pitches written in a specific pattern and order. Our Western “modern” music is based on 12 tones (or pitches) in each repeating “octave.” This is a “chromatic scale.” (If you listen closely to some Eastern music, for example, you can actually hear pitches between the 12 sounds of our western scale. The music may sound a little “confusing”; these extra notes is why.)

An octave is the point at which a note repeats the same tone just at a higher or lower pitch. The strings are vibrating at the same time. For example, pluck the bass “D” string and melody “D” string at the same time, they should sound as one pitch as they are vibrating together.

These 12 pitches represent all the white and black keys on a keyboard or piano. Counting from middle “C” to the next “C”, there are 12 keys (or notes). A guitar or banjo also has all these 12 notes. If you look at the fretboard of a guitar, the frets are equally sized; each representing one pitch.

What is a diatonic scale?

When you combine the white and black key for each note (i.e. C-natural and C#) on the 12-tone chromatic scale, you wind up with 7 tones (or pitches). These 7 notes are called a “diatonic scale” and they represent frets and notes on the dulcimer fretboard.

On the dulcimer fretboard, this configuration of notes begin at the “0” fret and go up to the “7” fret — skipping the “6” and using the “6-1/2 fret.”

You can sing the seven notes: do, re, me, fa, sol, la, ti do.

This is called the Ionian Mode and it also represents the pattern of notes used in the modern-day Major Scale.

And this is where things get complicated. Looking closely, there are two white keys (natural pitches) which don’t have an associated black key (or sharp note). These are the “E” note and “B” notes. They got short changed. Why? Who knows.

Here is another diagram to show the same whole and half step pattern with the 12 notes “condensed” to 7 notes:

It music theory, the notes with the white and black keys combined are called “whole” steps and the two notes with only a white key are called “half” steps. The whole steps take a larger space on the dulcimer fretboard, because they represent 2 pitches. (This diagram should look remarkably like the dulcimer fretboard.)

These pitches follow a specific pattern of whole and half steps: W, W, h, W, W, W, h.

Playing the D – Dorian Mode

What happens if you move up the keyboard, starting with the D note and play the 7-step scale using only the white keys (or the “natural” notes — no sharps or flats)?

This is called the D-Dorian Mode. Now there is a different pattern of whole and half steps. The pattern is: W, h, W, W, W, h, W. The “half” step moves closer to the beginning of the scale.

This subtle difference in the placement of these whole and half steps gives an entirely different “feel” to the music. The music sounds a little mysterious, moody, melachony. Although this is an ancient Greek scale, many contemporary songs use the Dorian mode. (See list below.) For example, “Riders on the Storm,” by the Doors is a song composed in the Dorian mode.

The Dorian Mode differs ever so slightly from a contemporary Minor Scale.

(Okay, for those who are technically inclined, the D Dorian Mode is like a D minor scale — both have a flatted third note. However, the Dorian mode has a raised sixth scale note — B rather than Bb. Both have these modes/scales have haunting and melocany sounds.) Don’t worry about this trivia — I like my simple diagrams better.

Playing the Dorian Mode on the dulcimer fretboard

There are two configurations of frets on the dulcimer fretboard where you can play the pattern of “whole” steps and “half” steps which match the Dorian pattern. These scale patterns all begin on either the 1st fret or the 4th fret.

(Trust me on the patterns, I looked at this until my eyes became dizzy.) Remember that D Dorian does not have sharp or flat notes. However, other “Dorian scales” starting with other notes must incorporate some sharp notes to keep the Dorian step pattern correct.

Here are some examples of Dorian mode arrangements on the dulcimer fretboard:

1. An easy way to play D Dorian Mode on the dulcimer is tune the dulcimer to DAC and begin at the 1st fret — go up to the 8th fret. Use the 6-1/2 fret. See that the scale uses only the “natural” notes — no sharps or flats.

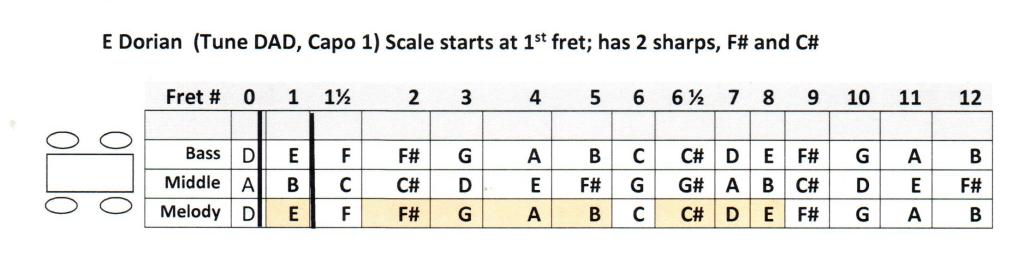

2. A second way is to tune to DAD and place a capo on at the 1st fret. This is E Dorian. (This scale does have two sharp notes since you are no longer starting with a D note. You have to compensate to keep the whole and half steps in sync.) Again, the scale begins at the 1st fret and goes up to the 8th fret (using the 6-1/2 fret).

3. I figured out that another way to play the D Dorian mode is by using the 1-1/2 fret and tuning the dulcimer to DAD. In this case, the scale starts on the bass string, “0” fret and goes across the strings. Still no sharps or flats!!

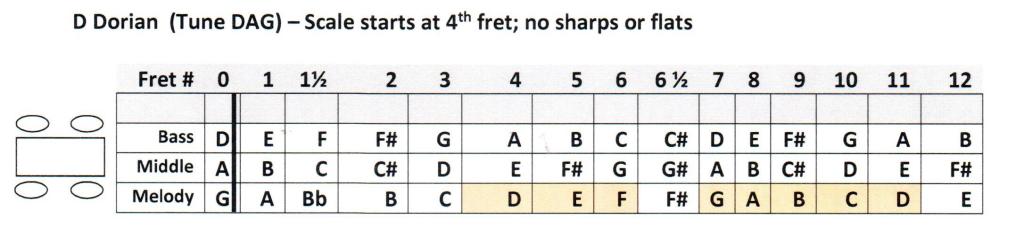

4. By tuning your dulcimer to DAG, you can now play the D Dorian mode starting at the 4th fret on the melody string. (Several songs in Neal Hellman’s book and Jean Ritche’s book use this tuning.) This is actually a great tuning to play songs in the Dorian mode; lots of room to go up and down the fretboard. Since these songs are very “modal”, they don’t need alot of harmony notes on other strings.

5. By tuning the dulcimer to DAD, you can play the A Dorian mode beginning at the 4th fret on the melody string. The A Dorian mode uses the F# note. (This was the tuning used by Mike Casey for “The Scotch Cap” song in his book — although technically he also used a C# note making his arrangement an Aeolian Mode.)

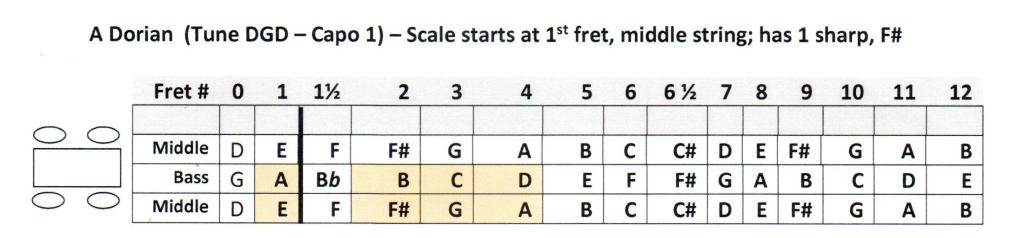

6. Finally, an often overlooked, but nevertheless useful way to play the dulcmer is by tuning the dulcimer to DGD with a capo at the first fret. The A Dorian scale starts on the middle string at the 1st fret. It includes an F# note. You can easily play “Cluck Old Hen” this way.

Seven ancient Greek modes:

There are seven of these ancient Greek modes (or scales): Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian.

For contemporary dulcimer music we mainly use:

- Ionian Mode — corresponds to major scale and begins at either the “0” to “7” fret or from the “3” to “10” fret.

- Mixolydian Mode – same as Ionian mode from the “0” to the “7” fret but uses the “6” fret and not the “6-1/2” fret. Think of “Old Joe Clark.”

- Dorian Mode – goes from the “1” fret to the “8” fret and uses the “6-1/2” fret.

- Aeolian Mode – goes from the “1” fret to the “8” fret and uses the “6th” fret.

Contemporary Songs in Dorian Mode

Many contemporary songs use the Dorian mode, as well as traditional ones. The music is melancholic and soulful which creates memorable “rifts” that engage the listener. The “raised” sixth note used in the Dorian mode gives a glimpse of being bright and hopeful.

Here is a list of songs which use the Dorian mode. I am sure there are many more songs which can be added to this list.

1. “Scarborough Fair” — Simon and Garfunkel — E Dorian

2. “Drunken Sailor” — Traditional English Sea Chanty Folk Song

3. “Cluck Old Hen” — Traditional Folk Song

4. “A Horse with No Name” – America

5. “Eleanor Rigby” – English rock band – the Beatles

6. “Billy Jean” — Micheal Jackson — F# Dorian and F#m

7. “Riders on the Storm” — The Doors — a psychedelic rock masterpiece that embodies the moody and atmospheric qualities of the Dorian mode — E Dorian

8. “Light my Fire” – The Doors — one of The Doors’ most iconic tracks — the song has a seductive, mysterious quality — A Dorian

9. “Wicked Game” – Chris Isaak — With an evocative melody and lush harmonic texture — B Dorian

10. “Thriller” by Michael Jackson — C♯ Dorian

11. “Nothing Else Matters” — Metallica — is a powerful ballad — E Dorian

12. “Smoke on the Water” — Deep Purple — G Dorian

13. “Mad World,” — originally by Tears for Fears and covered by Gary Jules — a poignant picture of despair and disconnection — F# Dorian

14. “Shakedown Street,” — Grateful Dead — E Dorian

15. “Get Lucky” – Daft Punk’ featuring Pharrell Williams, a modern disco-funk anthem that radiates positivity and infectious energy – B Dorian

16. “Another Brick in the Wall” — Pink Floyd — 1979

17. “Loser” — Beck – alternative rock with an eclectic mix of folk and hip-hop elements, contributing to its distinctive, slacker anthem vibe.

18. “Good Times” — Chic — a quintessential disco track radiates joy and optimism – E Dorian

19. “The End” — The Doors

20. “Drive” – REM

21. “Woodstock” – Joni MItchell — Eb Dorian

22. “So What” — Miles Davis

23. “Shady Grove” — traditional Appalachian

Playing “The Scotch Cap” on the Dulcimer

This English dance tune, “The Scotch Cap” is written in 6/8 time. It is a jig, so it can be played at a “peppy” tempo. That is, until the dancers slow down. However, rather than using an “in-out-in strum” as for Irish jigs, this song contains mainly dotted quarter notes and eighth notes. I find that a strum pattern which is “in-out,” “in-out,” works well, being mindful of the dotted quarter notes and eighth notes.

Remember that my tablature for this tune uses the 1-1/2 fret and not the 2nd fret. The song begins on the bass string. Pick the strings, as well as strum across the strings, as needed. The song doesn’t need harmony notes on the other strings. It is very “modal.” However, I did include suggestions for accompanying notes written above the standard staff for a second dulcimer player to play along with the jig’s melody.

“Deep Dive into Dorian Mode”

Enjoy this “deep dive” in to D Dorian tunes. I hope that you will find that my explanation is useful in describing why this tune sounds so different from a tune written using either a “major” scale or “minor” scale.”

I have included a chart of all my fretboard renditions of Dorian scales after the tablature for the tune. Download, enjoy and share with friends. Please just don’t publish or upload to public internet sites. (For Mike Casey’s tablature, purchase his book.)

References:

https://thesession.org/tunes/9621

https://www.pdmusic.org › Music Theory › Scales

https://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/del/sections/english_country_dance.html