I love the carefree American folk song, “The Big Rock Candy Mountain.” The song’s lyrics tells of a hobo who dreams of utopia where whiskey flows over the rocks and the box cars are all empty. Although I most closely associate the song with the movie, “O Brother, Where Art Thou?“, the tune has been around for a long time. In fact, it was copyrighted and recorded in 1928 by Harry McClintock. And the significance of that date is that, 95 years later, the song entered the public domain on January 1, 2024. And so, I made a dulcimer arrangment of this song. Whether or not a song is in the public domain, and obtaining permission to perform a song both can be very confusing topics. So, I researched the copyright issue and am including some of what I found.

About the song, “Big Rock Candy Mountain”

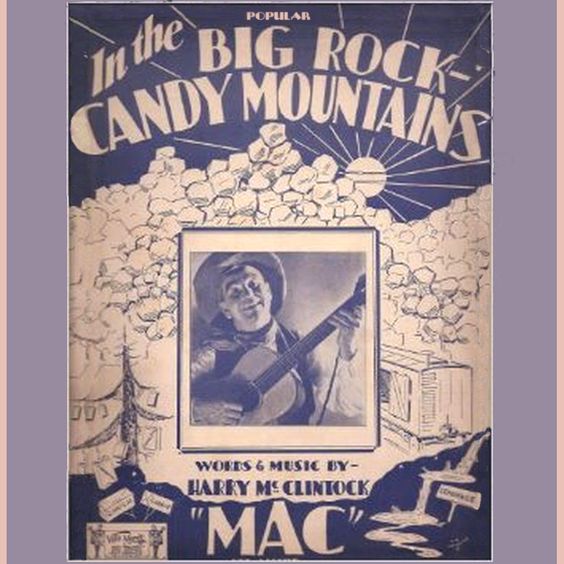

Harry McClintock (1884 – 1957) was a railroad man, radio personality, singer and songwriter. What an illustrious life he had. McClintock ran away from home as a young boy at the age of fourteen years and joined a circus. During his lifetime he worked on many railroads, was a union organizer, served as a civilian in US military in the Phillipines in the Spanish-American War, and traveled the world to Africa and Asia. He was a street musician in several cities and later became inolved hosting radio music shows including one for children after winning a singing contest.

The song, “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” is McClintock’s best know song and is based on his experiences working on the railroads as a brakeman. The song seems to parallel other folk song themes of that era including as well as those based on medieval paradise poems and songs called “Cockaigne.” In these ancient poems, physical comforts are always at hand and difficulties of medieval peasant life do not exist. McClintock’s song portrays this concept. At some point in time, McClintock identified the rock candy mountains as a range in south-central Utah. The mountains were given their name by railroad workers because of thee striped dun-and rose-colored hills. These mountains are from southern Colorado, but they are be similar to the ones in Utah found in McClintrock’s song.

In the early 1900s, McClintock was involved in an infringement lawsuit to protect his copyright of the song. At that time, he produced evidence to show that he had been singing versions of the song since the late 1800s claiming he wrote it as a young lad. However, McClintock copyrighted and recorded the tune in 1928 under his nickname, “Haywire Mac”, and so that is when the public domain date is determined. For McClintock’s recording, he scaled down the lyrics to a more acceptable version from more brazen ones regarding the life of a hobo. McClintock recorded the song several times but his music didn’t obtain commercial success as No. 1 on Billboard’s “Hillbilly Hits” chart until 1939.

Like other songs which have followed the folk music process, the tune has changed throughout the years. In fact, in 1949 an entirely different melody was recorded by Burl Ives. He used the same theme to the lyrics but adapted them for children. This is the melody which most of us recognize with the song today. Other contemporary artists, such as Tom Glaze (best known for for composing and recording “On Top of Spaghetti”), further modified the lyrics. Pete Seeger sang a version of “The Big Rock Candy Mountain” alternating his melody between both the original version and Burl Ive’s version.

So, although the original version from McClintock is now in the public domain, is seems that the more contemporary version which we sing today by Burl Ives is probably still copyrighted.

Permission to Use and Play Music

The topic of obtaining permission to make printed copies of music and to perform the music in public seems to be a very confusing one for many dulcimer players. So, here is what I know.

Written music, like other written literature, is copyrighted for a certain length of time. In order to make copies of a piece of music, you need to get permission from the author or publisher. Eventually, copyrights expire and the music enters the public domain where anyone can use the music.

In order to perform the music in a public place, you need a second type of permission — you must obtain a license to perform the music. Hence, two different types of permissions are involved in using music.

Regarding licenses to perform music, a person (or their agent–such as a descendent of the person) who has a copyright on a piece of music may license others to use and play their work. In researching this topic, I discovered that there are actually six different types of licenses which pertain to playing someone else’s music. Dulcimer players are most often concerned with two of these rules: copying music (discussed in the second paragraph above and below) and then playing it in a public place. The other regulations pertain to topics such as recording the music on a compact disk or using the music in a commercial or video.

Copyright Laws and Public Domain

Copyright laws give protection to copying and performing music to the exclusive right of the copywright owner (usually the musician or publisher). In other words, a person needs to get permission before making printed copies of a copyrighted work and to playing it if the music is not in the public domain.

How long does a copyright last? The law has been amended over the years, which adds to the confusion. So, the answer is, “it depends” on when the music was composed.

Works created prior to 1978 generally have a copyright protection length of 95 years. This assumes that the owner made all the applicable copyright renewals over the years. (The music owner must renew their copyright at certain intervals.) For practical purposes, it means that copyright protection for songs written in 1928 expire in 2024. In other words, anything composed on or prior to 1928 is now in the public domain.

The law is different for music composed after 1978.

“The length of copyright protection depends on when a work was created. Under the current law, works created on or after January 1, 1978, have a copyright term of life of the author plus seventy years after the author’s death. If the work is a joint work, the term lasts for seventy years after the last surviving author’s death. For works made for hire and anonymous or pseudonymous works, copyright protection is 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever is shorter.“

(www.copyright.gov/what-is-copyright/#:~:text=U.S.%20copyright%20law%20provides%20copyright,rental%2C%20lease%2C%20or%20lending)

What are phonorecord laws?

Phonorecords are sound recordings of music. Sound recordings of music have slightly different copyright rules from written music scores. Those copyright lengths and rules pertaining to phonorecords are given elsewhere on-line.

According to the Musician’s Institute Library, “”Copyright duration for sound recordings changed in 2018 due to the passing of the Orrin G. Hatch-Bob Goodlatte Music Modernization Act (or Music Modernization Act or MMA for short). Title II of this law covers the protection of sound recording pre-1972, which were not federally protected previously.” (library.mi.edu/musiccopyright/duration)

Permission to Perform Music in Public

To perform music in public, you generally must obtain a license from the copyright holder (or his agent) according to a set of licensing regulations. Rather than dealing with each individual composer to obain permission to play a song, agencies which represent the rights of composers and music artists have evolved. The most prevelant licensing agencies (called performing rights organizations or PROs) are ASCAP, BMI and SESAC (country music oriented). And there are several smaller PROs. A musician/composer joins one or more of these organizations who then collect fees each time the song is played by someone who has obtained a license. ASCAP, BMI and/or SECAP then pays the musician/composer a portion of the proceeds from the concert.

In this system, a concert sponsor or group — such as a dulcimer club — obtains a license from one or more of these organizations (ASCAP, BMI and or SESAC) to play music in public or host a concert. The concert sponsor (dulcimer club) reports quarterly what concerts/performances are given, and pays a certain amount of money based on a formula related to on what songs are played, audience attendance and concert admission fees. Then the musician/composer is paid by ASCAP, BMI and/or SECAC based on money collected from the licensed group (dulcimer club).

It is important to understand several issues when dealing with performance licenses:

1. It is not the musician who is playing the song in public who obtains a license from ASCAP, BMI or SESAC. Rather, it is the organization or entity who is responsible for promoting/hosting the concert or public event who obtains the license. There are many types of licenses — radio stations, for example, have a difference type license than a non-profit dulcimer club who is sponsoring a concert. If the dulcimer club who is sponsoring the concert, then the club needs the license. However, if you are asked to play for a community organization or a church, for example, then generally that group needs the license.

2. In addition, not all musicians/artists belong to the predominant agencies — ASCAP, BMI or SECAP. Or, the may belong to two of these agencies. Plus, there are other licensing agencies in addition to these three agencies.

For example, we discovered that zydeco artist, Clifton Chenier, doesn’t belong to any of these three main agencies. Many of Chenier’s master sound recordings were sold to the Smithsonian Folkways Recordings Institution which is the nonprofit record label of the Smithsonian Institution. However, in an E-mail to Smithsonian, they state that they only hold the sound recordings, not the publishing rights. In reasearching this further, it appears that Clifton Chenier’s music was copyrighted by Tradition Music Co and administered by BUG Music Cmpany and recorded by Arhoolie Production, Inc owned by Chris Strachwitz. In 2011, BUG Music Co was sold to BMG, a huge international music publisher and recording company based in Berlin, Germany. So, we would need to get permission from BMG to use Chenier’s music. The jacket insert of a recording is a good place to start to get information about the songs. Here’s one excerpt:

“All songs by Clifton Chenier and copyrighted by Tradition Music Co. administered by BUG Music Co. BMl Edited and produced by Chris Strachwitz Cover: Clifton Chenier in 1964; Cover photo by Chris Straclm itz Cover & photo tinting by Beth Weill Recorded in I.ouisiana. Texas, and California between 1964; and 1983. All selection; Arhoolie CD 1964 & 1997 by Arhoolie Production;, Inc.“

3. Once a license is obtained from ASCAP, BMI, SECAP or others you self-report quarterly to these organizations and pay a fee based on a formula. You must know, not only the name of the song, but the specific version and the name of the singer and/or arranger of that version so that the correct person can get their fees. Things get complicated very quickly.

4. From our club’s experience with ASCAP and BMI, we learned that the licenses cost about $250/year to each organization plus money paid for each concert. The licenses renew automatically from year to year, making a substantial monentary investment.

5. These licensing organizations ASCAP, BMI and SECAP (and others) want to know what you played even if you played the concert was “free” admission. You need to report quarterly every time a concert or public event is given.

Should a dulcimer club get a license from one or more of these groups (ASCAP, BMI and SECAP)? I can’t answer that question. Each dulcimer club needs to decide that issue.

Not sure if a song is the public domain?

Do an internet search. With some tenacity and searching, you can usually determine whether or not the song is in the public domain and who holds the rights to the song.

Here’s a site which gives lots of good information about tunes:

Public Domain Information Project: https://www.pdinfo.com/index.php

Here’s another site: Songview — a combined site of ASCAP and BMI https://repertoire.bmi.com/

Remember, this site is for specific artists’ recordings of songs. For The Big Rock Candy Mountain, these are artists which recorded versions of the song; the original song is still in the public domain.

What about copying dulcimer tablature?

What about copyrighting dulcimer arrangements of music? Although a dulcimer player can’t copyright a song which is in the public domain, it is my opinion that their own tablature arrangement — given that it is unique and identifiable — should be considered their own work falling under copyright publishing guidelines. It is important to understand that a person doesn’t have to obtain a physical copyright from the Library of Congress in order to own his work. Once his composition is written and printed, etc, it essentially “copyrighted.”

Much dulcimer music tablature is handed out at workshops and on-line forms. Dulcimer players and clubs have traditionally made copies freely of this music. However, we are becoming more knowledgable about copying music and copyright issues. Someone who wants to make multiple copies of music for their entire group should, a common courtesy, have an understanding and permission from the author as to how many copies of the tablature can be made. Dulcimer musicians vary greatly in what they consider to be appropriate. Some dulcimer musicians don’t mind that copies of their music are shared. Other musicians ask that their music be purchased, especially if it is in a published book. Check to be safe. Likewise, the dulcimer is a social and group instrument. Musicians should be aware of that aspect of playing the dulcimer when sharing their music in workshops.

Dulcimer Tablature for Big Rock Candy Mountain

Harry McClintrock recorded this song as a arrangement of singing with a flatpicked accompaniment on a guitar. No band or percussion. It was simple but effective. It has the feel of a folk song, not a bluegrass tune. For dulcimer, either fingerpick, flatpick or strum. It is easy to check out You-Tube versions to listen to McClintrock playing his song.

I have included a dulcimer tablature version of Harry McClintock’s “Big Rock Candy Mountain” but not Burl Ive’s version — which is the more common tune. That one appears to still be copyrighted.

There are many ways to arrange this song for the dulcimer. I included several different harmony note combinations as well as suggested chords (shown above the standard music line). This is a template — feel free to change it up, especially if you are singing. For the dulcimer, the song needs harmony notes or chords to make it come alive. This is not a dronal song.

If strumming, I suggest keeping up a good strumming rhythm and filling in strums as needed.

In summary, copyright laws can be a confusing topic. Keep in mind that making printed copies of music (permission from publisher/agent/composer) is a different set of rules from playing a song in public (unless it is in the public domain) — for which you need a license. It is worth your time to research and learn about this topic. With some tenacity and searching, you can usually determine whether or not the song is in the public domain and who holds the rights to the song.

This carefree and melodic tune is a fun one to sing and play. Let’s learn this on the dulcimer. I have included jpeg images of the song as well as a PDF file which can be downloaded for your enjoyment to learn, play and share with others in your group.

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Big_Rock_Candy_Mountains

https://fredbals.medium.com/oh-that-big-rock-candy-mountain-254ff946e078

https://www.musicbed.com/knowledge-base/types-of-music-licenses/28

First let me thank you for your arrangements each month.

<

div>Second, when I go to the link th

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello, Sorry looks like your comment got cut off. Maylee

LikeLiked by 1 person

Second when I read your monthly article it goes to my browser and will not stay on the page. It keeps going back to the beginning. Third what are the arrows in the tab?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello MIke, I just wanted to say that I checked all my links to outside internet sites; they all work — just make sure that you have removed the comma after com. — I did now but that probably won’t show in your browser. I copied and pasted the links to another window. I don’t know why your post keeps going to the top of the page. So sorry about that and iI hope you can figure it out, I am guessing you clicked on “read more”, I think that may be a computer issue. As my husband says, when in doubt, reboot the computer! The arrows are just remiders to hold those notes down until you get to the next fret change rather than lifting your fingers up off the frets up. Unlike other folks who write tab, I leave out tab numbers if they remain the same, it just makes it easier to read, but the intent is to keep playing those chords or tab. Hope this helps; enjoy the tab. Maylee

LikeLike